Unraveling the Housing Dilemma: Income Disparity and Market Forces

Understanding the Root Causes of Housing Unaffordability

For an extended period, policymakers and researchers have been dissecting the elements contributing to the escalating housing affordability challenges across the nation. While some attribute the issue to regulatory hurdles like zoning ordinances and land-use restrictions, and others point to limitations in construction capacity or rising interest rates, a deeper, systemic problem appears to be at play: the stagnation of wages relative to the cost of living.

The Disconnect Between Earnings and Living Costs

This growing disparity between what people earn and what they need to spend to live is, according to prominent experts in housing and labor economics, central to comprehending why the aspiration of owning a home is becoming increasingly unattainable for many Americans. Their insights suggest that the crisis extends beyond merely the price of real estate; it is intricately linked to how income is distributed, the compensation levels for labor, and the entities controlling investment flows within the housing sector.

The Far-Reaching Consequences of Diminished Earnings

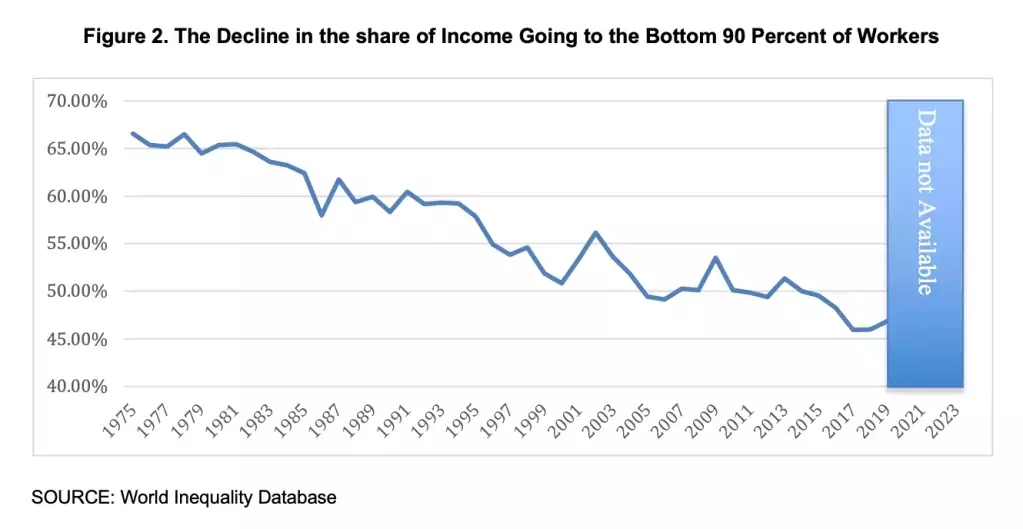

Research by Carter C. Price, a senior mathematician at the RAND Corp. and a professor of policy analysis, illustrates a significant reduction in the portion of national income allocated to the lower 90% of the workforce. Price noted that, despite recent minor increases in wage growth, these gains are insufficient to counteract the cumulative losses experienced over five decades. His analysis reveals that the widening income disparity has imposed substantial financial burdens on working households.

The $79 Trillion Shortfall: A Legacy of Lost Income

If the income distribution in the U.S. had remained consistent with 1975 levels, the bottom 90% of earners would have collectively received approximately $3.9 trillion more in 2023 alone. Over the entire period from 1975 to 2023, this deficit totals an astonishing $79 trillion in foregone income. Price's team estimated that the median American household would have earned about $29,000 more in 2018 under such conditions, a figure that has likely grown since.

Stagnant Wages: A Barrier to Homeownership

Price emphasizes that this reduction in earning potential directly impedes opportunities for homeownership. He argues that even if households could save a fraction of this additional income, it would significantly boost their ability to afford down payments. He further points out that even with decreases in mortgage rates, stagnant wages continue to lock numerous households out of the housing market.

The Evolution of Housing Finance: From Local to National

Laurel Kilgour, an attorney and research manager at the American Economic Liberties Project, identifies a parallel development in the structure of housing finance. She explains that decades of consolidation and deregulation have eroded the community-based lending systems that once supported smaller homebuilders. This shift, she contends, has made it increasingly difficult for smaller builders to secure the necessary capital.

The Influence of Financialization on Housing and Wages

Both experts concur that financialization—the increasing dominance of financial markets and motivations—is a common thread connecting stagnant wages and the often-insurmountable costs of housing. Kilgour highlights that reduced competition among employers, a result of market concentration, contributes to suppressed wages. She also points to the impact of trade policies and job offshoring as exacerbating factors. Price's data supports this, indicating robust corporate profits despite a declining share of income for labor, leading to uneven wage growth that pushes home prices in major metropolitan areas beyond the reach of middle-income buyers.

The Rise of Build-to-Rent and Institutional Ownership

Kilgour also addresses the growing trend of institutional investors purchasing homes and developing neighborhoods specifically for rental purposes. This phenomenon, she warns, is profoundly impacting regions where families are increasingly unable to buy homes, transforming communities into rental-dominated areas. Price agrees, stating that if worker wages had kept pace with the broader economy, the housing landscape would likely feature fewer luxury condominiums and more single-family homes designed for the middle-income segment.

Healthcare Costs: A Hidden Economic Burden

Kilgour further identifies healthcare expenses as a silent drain on wages. She notes that the high cost of the U.S. healthcare system significantly suppresses wages, affecting both employers and employees alike. Both parties, she suggests, would benefit from reforms addressing this issue.

The Social and Political Ramifications of a Nation of Renters

Looking ahead, Kilgour cautions that a continued decline in homeownership could lead to significant political and social upheaval in the U.S. She laments the diminishing bipartisan recognition of homeownership's importance, which once fostered civic harmony and shared prosperity. She warns that making people live in more precarious situations ultimately creates a more unstable society for everyone.

Wealth Accumulation and the Future of Homeownership

Price reinforces this by explaining that income directly translates into wealth over time. The slower growth of incomes for those below the 90th percentile makes it harder for this demographic to save enough for significant investments like real estate. Both experts conclude that unless wages accurately reflect overall economic growth, the housing market will continue to favor investors over families, and the American ideal of homeownership will progressively diminish. Kilgour poignantly summarizes, "Home ownership is partly about having a sense of dignity and stability — and when that’s stripped away, we all pay the price."