Brining vegetables can dramatically improve their taste and consistency, a simple technique that has been often overlooked. While traditional brining focuses on meats, applying this method to a variety of vegetables can unlock new culinary possibilities. The scientific principles of osmosis and diffusion, where salt and water interact with vegetable cell walls, are key to understanding how brining transforms produce. This comprehensive guide explores which vegetables respond best to brining, the ideal salt concentrations and durations, and the surprising benefits for both common and less-expected items, ultimately demonstrating that this preparation step is a worthwhile addition to any cook's repertoire.

The culinary landscape often places vegetables in a supporting role, yet with a bit of foresight and the art of brining, they can become stars of the dish. This article delves into the transformative power of brining, showcasing how a simple saltwater solution can elevate the flavor profile and texture of various vegetables. From green beans to sweet potatoes, the research highlights specific brining techniques, optimal timings, and salt concentrations that yield exceptional results. By embracing brining, home cooks can turn ordinary vegetables into extraordinary culinary experiences, adding depth and complexity that complements any meal.

The Science Behind Vegetable Transformation

In the culinary world, brining is commonly associated with enhancing meats, offering solutions for dryness or blandness. However, its application extends surprisingly well to vegetables, significantly improving both taste and texture. This process relies on fundamental scientific principles like diffusion and osmosis, where salt penetrates vegetable cells and influences their water content. While meat brining focuses on protein denaturation for tenderness, vegetable brining primarily aims to concentrate flavors and modify cellular structure. For instance, salting eggplant or cucumbers is a long-standing practice that either firms up or tenderizes the produce by drawing out excess water, leading to a more intense flavor. This article examines whether such benefits can be extended to a wider array of vegetables, including those often considered "waxy" or starchy like broccoli, cauliflower, carrots, and potatoes, challenging conventional kitchen wisdom.

The core mechanism of vegetable brining lies in the interplay of salt and water across cell membranes. Diffusion involves the movement of salt from a high-concentration area (the brine) into the lower-concentration interior of the vegetable, thereby seasoning it from within. Simultaneously, osmosis draws water out of the vegetable cells into the higher-salt environment of the brine, a process crucial for vegetables intended for pickling or fermentation, like sauerkraut. This water removal concentrates the vegetable's natural flavors and can alter its texture. While brining meat affects fibrous proteins, vegetables lack these and instead contain polysaccharides, sugars, and starches. Their semi-permeable cell walls allow salt and water exchange, but the effectiveness varies depending on factors beyond just water content, such as the presence of epicuticular wax on the skin. This waxy layer, found on most produce, acts as a natural barrier, repelling water and protecting against pathogens. For optimal brining, especially for less permeable vegetables, peeling, cutting, or physical manipulation (like smashing) is often necessary to expose the inner flesh and facilitate the brine's interaction, ensuring thorough seasoning and texture modification.

Optimal Brining Strategies for Diverse Produce

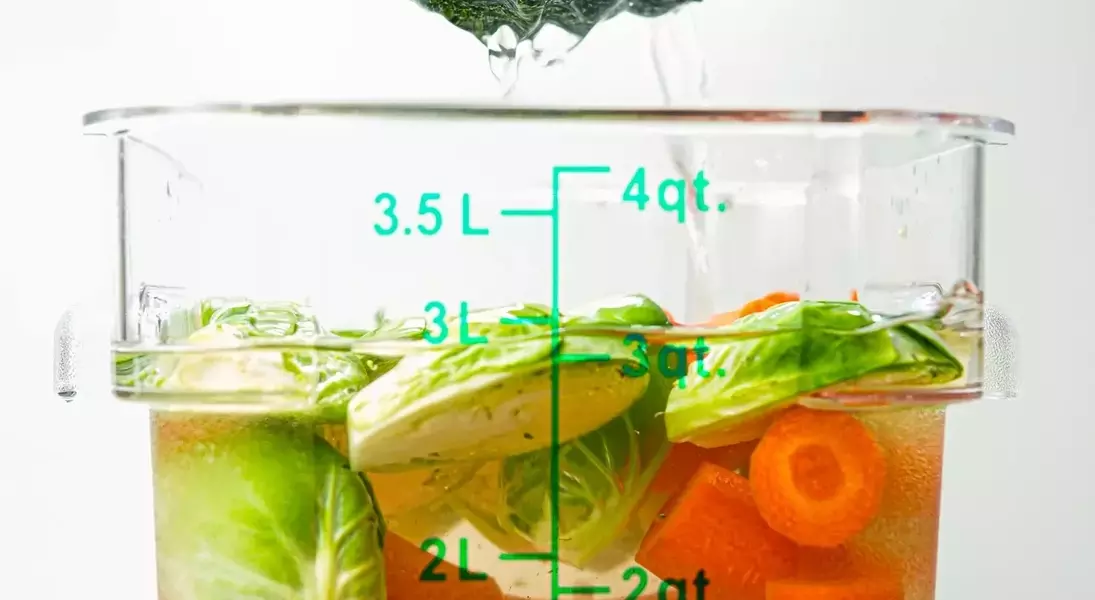

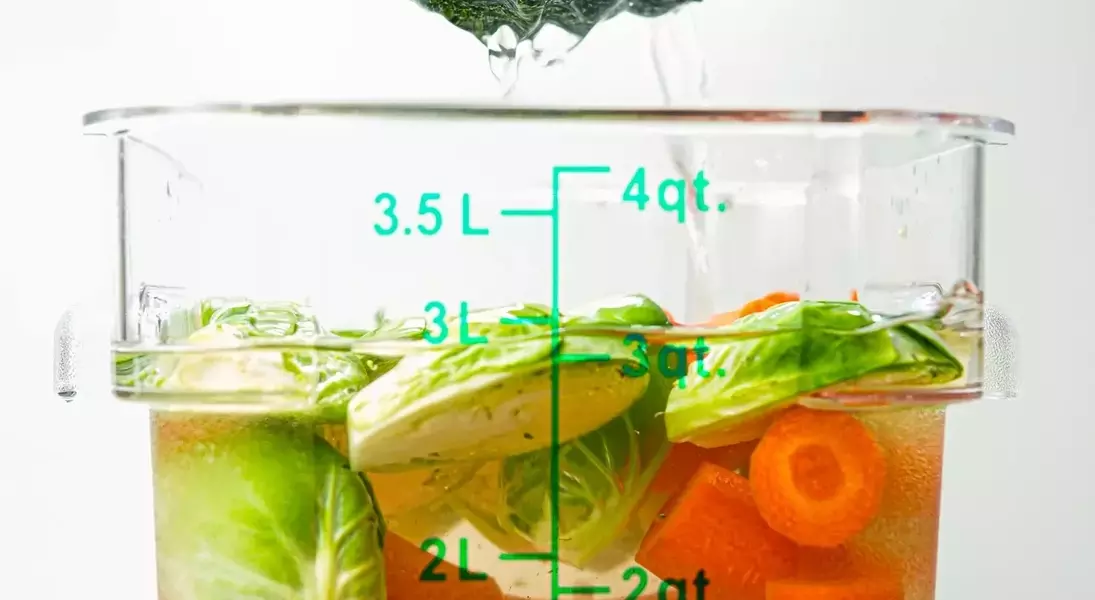

The quest to optimize vegetable flavor and texture through brining led to extensive testing across a wide range of produce. The central hypothesis was that nearly any vegetable could benefit from brining under the right conditions, yielding noticeable improvements in taste and consistency. This involved submerging various vegetables in salt solutions of differing concentrations (5%, 8%, and 10%) for varying durations, from 30 minutes to 12 hours. To ensure maximum salt transfer, vegetables with skins were peeled or cut to expose their inner flesh. After brining, samples were cooked using methods like roasting or broiling, then evaluated for changes in weight (indicating water loss or gain), flavor, and texture. This systematic approach revealed distinct benefits and optimal practices for different vegetable types, highlighting the versatility and impact of thoughtful brining.

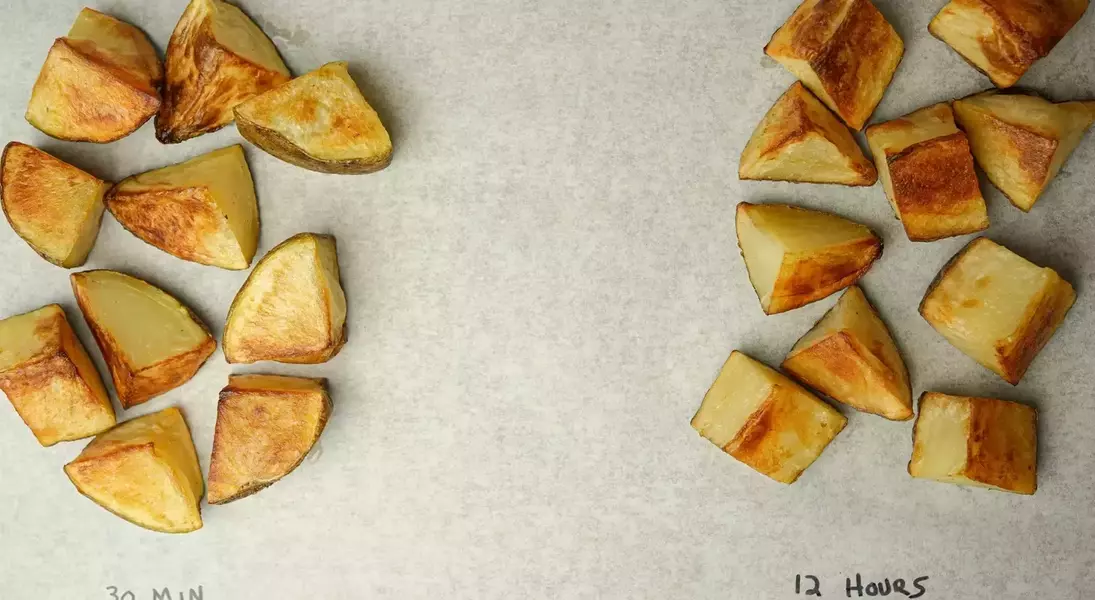

Specific vegetables responded uniquely to the brining process. Green beans, for example, benefited most from shorter brining times (1-4 hours) at an 8% salt concentration, achieving ideal seasoning without becoming excessively salty or wilty, making them perfect for high-heat cooking. Russet potatoes, when peeled and cut into chunks, developed a creamier interior and more even seasoning after 30 minutes to four hours in a 5% to 8% brine, a result influenced by water absorption as much as salt. Cruciferous vegetables like broccoli and cauliflower, when brined as whole crowns for about four hours, became sweeter, less bitter, and more evenly seasoned. For faster results, separating florets and brining for up to one hour proved effective. Sweet potatoes, with their lower water content, also achieved a creamier texture and improved seasoning after up to four hours in a 5% to 8% brine. Brussels sprouts, when halved and brined for one to four hours in up to a 10% solution, exhibited sweeter, less bitter flavors, a creamier texture, and more even browning, challenging the notion that brining only affects water-rich vegetables. These results underscore that while brining isn't a universal solution, careful application can transform a wide array of vegetables.