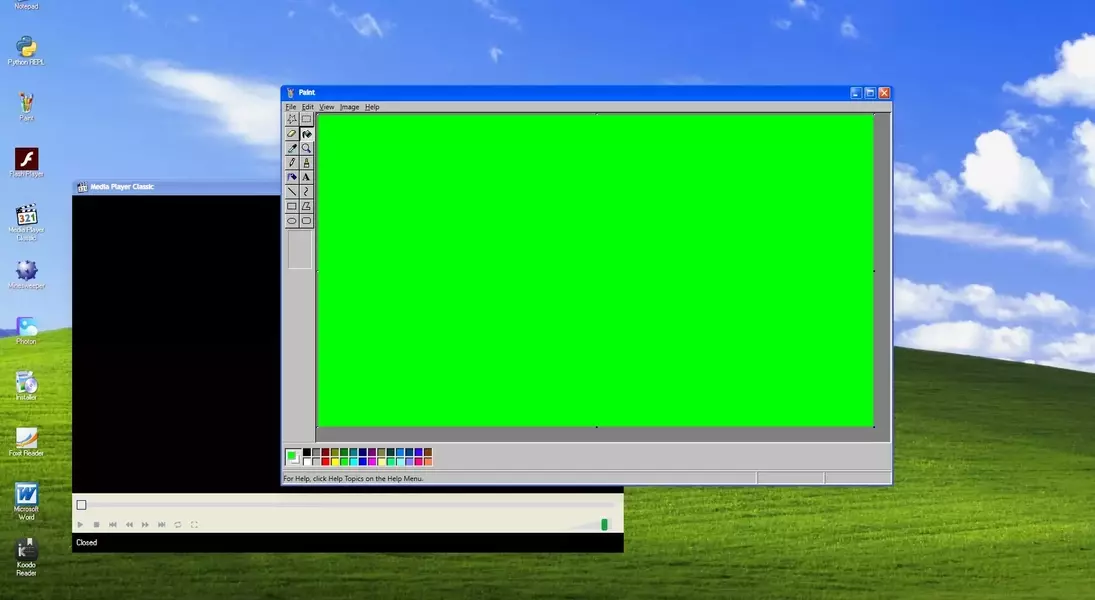

In the early days of personal computing, playing videos smoothly was a significant challenge. This article delves into the ingenious, and somewhat deceptive, method older Windows operating systems employed to achieve this. By utilizing a "green screen" or chroma-keying technique, Windows 95, 98, and XP were able to render video content efficiently, a practice revealed by a former Microsoft engineer. This sophisticated approach involved projecting video frames onto an invisible graphics surface, which was then seamlessly integrated into the desktop display. This not only ensured consistent performance but also led to interesting quirks, such as screenshots capturing green areas instead of the actual video feed, a testament to the clever trickery embedded within the system's architecture.

Unraveling the Mystery of Early Windows Video Rendering

A fascinating insight into the technical wizardry behind vintage Windows systems has recently come to light, courtesy of veteran Microsoft developer Raymond Chen. His revelations shed new light on how Windows Media Player in versions like 95, 98, and XP seemingly 'lied' to users about how it rendered video content. Far from displaying video directly within its window, the operating system cleverly employed a technique similar to modern-day chroma-keying, or 'green screen' technology.

Instead of sending video pixels directly to the display window, Windows would generate a placeholder, typically a green screen, which acted as a canvas. Simultaneously, the actual video frames were rendered onto a separate, shared graphics surface that was tightly integrated with the graphics card. The crucial step involved instructing the graphics card to replace any green pixels it encountered within the designated area with the corresponding pixels from this shared video surface. This entire process was largely invisible to the user, creating the illusion of direct video playback within the application window.

This 'overlay' method offered several distinct advantages. It elegantly bypassed the need for complex pixel format conversions, which could be resource-intensive, especially when the video's native format differed from the monitor's display capabilities. Furthermore, by decoupling the video rendering process from the user interface thread, Windows ensured uninterrupted video playback, even if the operating system's shell experienced temporary freezes or lags.

A more advanced iteration of this technique, known as 'flipping,' further enhanced performance. It involved using two shared graphics surfaces: one holding the currently displayed video frame and another pre-loading the subsequent frame. The graphics card would then rapidly switch between these surfaces during the monitor's vertical refresh cycle, ensuring exceptionally smooth transitions between frames.

However, this sophisticated method also led to some peculiar user experiences. Notably, if a user attempted to capture a screenshot of a playing video, the resulting image would often display green areas where the video should have been. This occurred because the screenshot utility captured the desktop's rendered state, which, at that point, still contained the green placeholders before the graphics card performed the video overlay. If the captured image was then opened in an application like Paint while the media player was still active and positioned over the same screen area, the active video's frames would once again invisibly replace the green pixels in the Paint window, demonstrating the persistent nature of the overlay system. Moving the Paint window or closing the media player would reveal the green pixels in their true form.

While modern computing power has rendered such intricate video rendering techniques largely obsolete, with contemporary operating systems directly handling video playback with ease, this historical anecdote provides a fascinating glimpse into the innovative solutions developers crafted to overcome technological limitations in the past. It also highlights how a seemingly simple act like video playback was once a complex dance between software and hardware, full of hidden mechanisms.

The intricate solutions developed for early Windows video playback offer a valuable lesson in creative problem-solving under technical constraints. It’s a testament to the ingenuity of engineers who, faced with limited processing power, devised elegant workarounds like chroma-keying and graphics overlays to deliver a seamless user experience. This historical insight can inspire current developers to think innovatively, reminding us that sometimes, the most effective solutions are not always the most direct ones. Moreover, it underscores the rapid evolution of technology and how capabilities that were once considered advanced or even 'tricks' have become standard features, illustrating a continuous cycle of innovation and adaptation in the tech world.