As New York commemorates the bicentennial of the Erie Canal, a pivotal infrastructure project that transformed the region, there's a concerted effort to acknowledge the profound and often painful impact it had on Indigenous communities. This year's events aim to move beyond a purely celebratory narrative, incorporating the untold stories of dispossession and cultural loss experienced by the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Through educational programs, symbolic gestures like white pine tree plantings, and a replica boat journey led by Indigenous voices, the bicentennial seeks to foster a more complete understanding of this complex historical period, sparking vital conversations about historical injustices and their lasting legacy.

New York Faces Complex History During Erie Canal Bicentennial

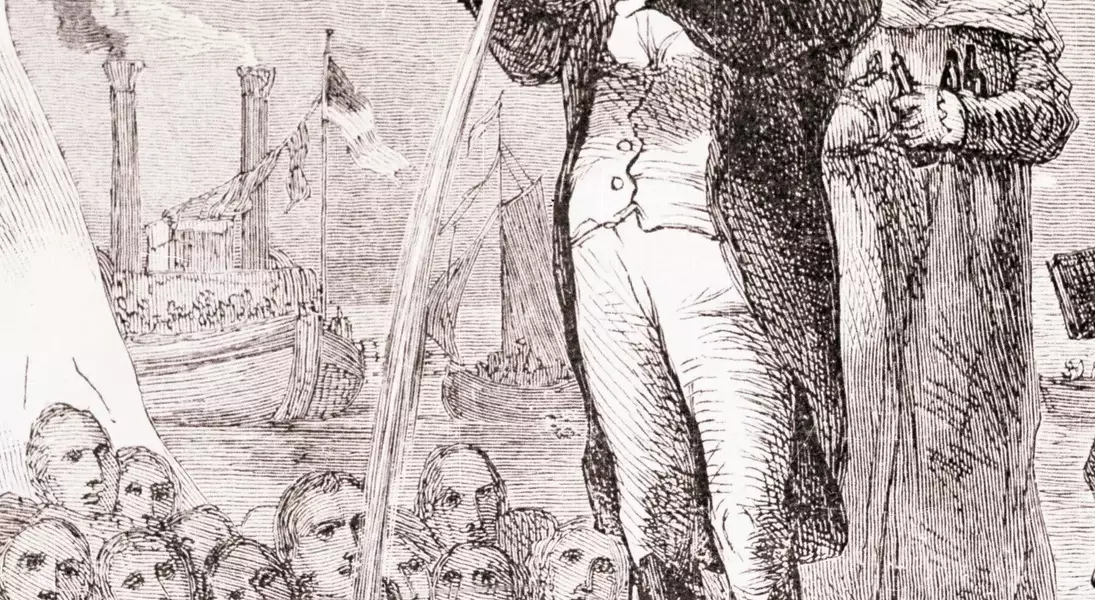

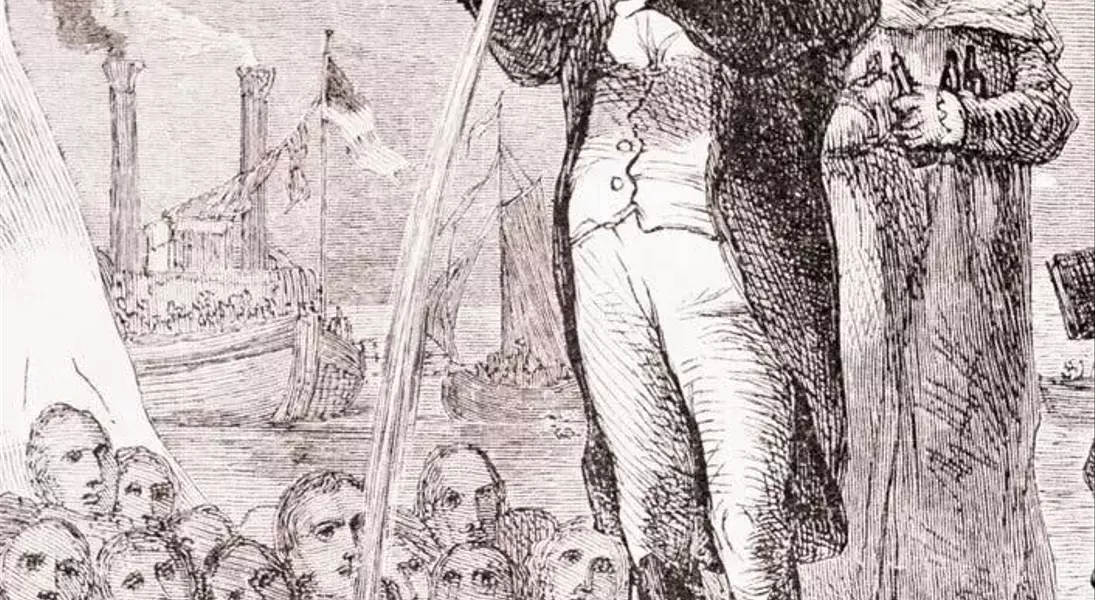

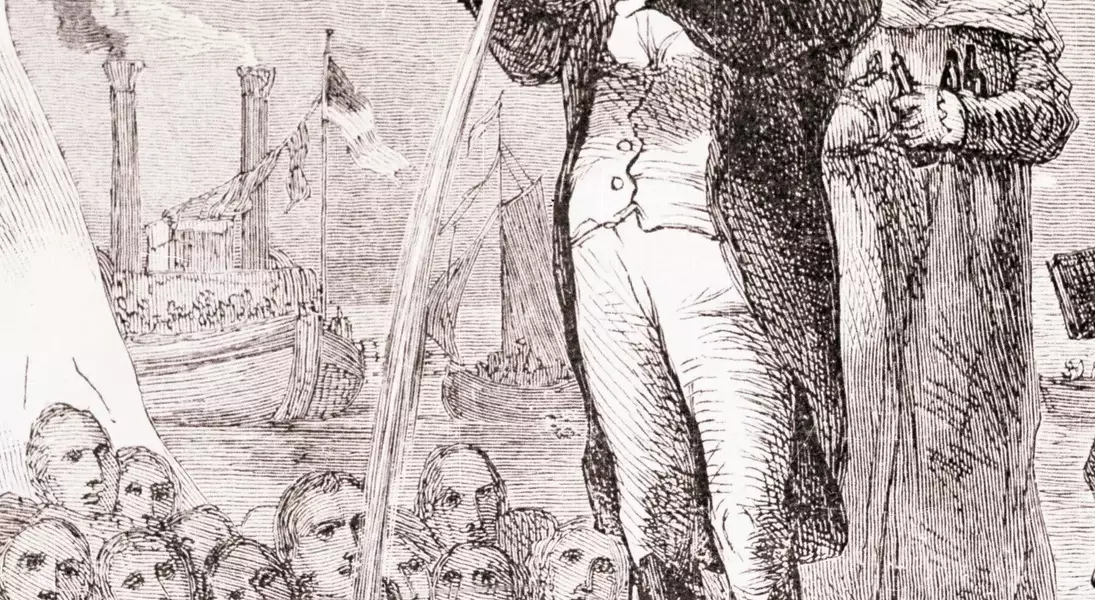

In October 1825, a momentous occasion unfolded as New York Governor DeWitt Clinton inaugurated the Erie Canal, a 360-mile artificial waterway connecting Lake Erie to the Hudson River. This ambitious project, though celebrated as an engineering marvel and an economic catalyst, also initiated a painful chapter for the Indigenous communities of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, whose ancestral lands lay along the canal's route. While Clinton's boat, the 'Seneca Chief,' symbolized progress, another vessel, 'Noah's Ark,' carried members of the Seneca Nation alongside animals, a dehumanizing spectacle that foreshadowed their impending displacement.

As New York marks the canal's 200th anniversary this autumn, events are designed to blend celebration with a crucial re-examination of history. A significant initiative involves planting Eastern White Pine trees, a Haudenosaunee peace symbol, along the canal's length from Buffalo to New York City. This gesture recognizes the considerable harm inflicted upon the Haudenosaunee, whose traditional territories were largely seized through coercive negotiations. The canal's opening facilitated a surge of white settlers, intensifying the demand for Indigenous lands, often through fraudulent treaties.

This renewed focus on Indigenous dispossession aligns with a broader national discourse surrounding historical injustices. While some states have enacted laws limiting discussions on such topics, New York has demonstrated a willingness to confront its past. Notably, in May, Governor Kathy Hochul issued a formal apology to the Seneca Nation for the 'historic atrocities' committed at the Thomas Indian School, a state-run boarding school that forcibly enrolled thousands of Indigenous children.

The bicentennial's expanded narrative includes programs at the Erie Canal Museum in Syracuse and other institutions, featuring Haudenosaunee speakers and events. On September 24, a replica of the 'Seneca Chief' embarked from Buffalo on its journey to New York City. The inaugural speech was delivered by Joe Stahlman, a historian of Tuscarora descent, emphasizing the importance of reflecting on the canal's full meaning over two centuries.

However, this focus on the negative consequences has not been without criticism. Mark Poloncarz, the Erie County executive, expressed concern that a Buffalo History Museum exhibit, 'Waterway of Change,' too heavily emphasized the harm to the Haudenosaunee, overshadowing the canal's importance to Buffalo and the nascent nation. Yet, Brian Trzeciak, executive director of the Buffalo Maritime Center, responsible for the 'Seneca Chief' replica, asserts the necessity of an 'expanded narrative' that acknowledges both the canal's achievements and the suffering it caused.

The white pine tree planting ceremony, held three days before the replica's launch at Seneca Bluffs Natural Habitat Park, within the historic Buffalo Creek Reservation—land infamously acquired from the Senecas through a fraudulent 1838 treaty—underscores this commitment. With white pines capable of living for over two centuries, these saplings serve as living monuments, offering future generations a poignant reminder of a complex history, and a call for ongoing healing and honest dialogue, as articulated by Melissa Parker Leonard, a descendent of the Seneca Nation.

The bicentennial of the Erie Canal presents a profound opportunity for collective introspection. It compels us to recognize that monumental achievements often come with hidden costs, particularly for marginalized communities. This historical moment serves as a powerful reminder that true progress involves not only celebrating triumphs but also courageously confronting and acknowledging past injustices. By embracing a more inclusive and nuanced understanding of history, we pave the way for genuine reconciliation and build a more equitable future, where the voices of all are heard and respected. The planting of the white pines symbolizes not just remembrance, but a commitment to enduring peace and the ongoing healing process.