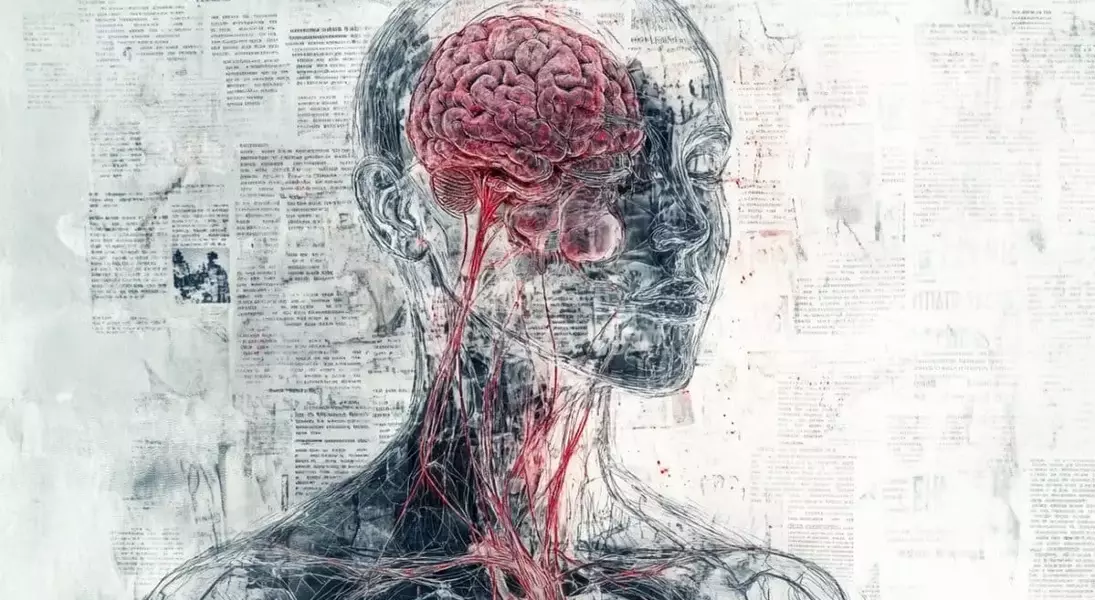

A groundbreaking study conducted by the University of Oklahoma reveals that survivors of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing continue to bear physiological imprints of trauma, even decades later. Despite leading healthy and resilient lives with minimal psychological symptoms, these individuals exhibit subtle yet significant changes in their biological stress markers. The research highlights altered cortisol levels, blood pressure, heart rate, and inflammatory interleukins, suggesting a lingering impact on the body's stress and immune systems. This finding underscores the disconnect between emotional recovery and physical responses, emphasizing the need for further investigation into the long-term health implications of trauma.

Researchers examined three distinct biological systems in survivors who were heavily impacted by the bombing. Compared to a control group unaffected by the event, survivors demonstrated lower cortisol levels, higher blood pressure, and a reduced heart rate in response to trauma cues. These findings indicate a blunted physiological response over time, despite participants reporting resilience and low scores for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression. Two specific interleukins were measured: interleukin 1B, linked with inflammation, was significantly elevated in survivors, while interleukin 2R, which plays a protective role, was found to be lower. This imbalance raises concerns about potential long-term health risks, even in otherwise healthy individuals.

Lead author Phebe Tucker, M.D., an emeritus professor of psychiatry at the OU College of Medicine, explained that while the mind may recover and move past traumatic events, the body retains a memory of the experience. "The main takeaway is that although the mind can be resilient, the body does not forget," she stated. Surprisingly, there was no correlation between the observed biomarkers and the psychological symptoms reported by the participants. This suggests that the body's stress response operates independently of expressed emotions, highlighting the complexity of trauma's lasting effects.

The study draws upon data collected seven years after the bombing, making it unique in its examination of stress biomarkers in medically healthy survivors of the same traumatic event. Co-author Rachel Zettl, M.D., clinical assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the OU College of Medicine, emphasized that severe trauma fundamentally alters biological systems, changing one's physical being. The research team, including notable contributors such as Betty Pfefferbaum, M.D., and Carol North, M.D., aims to deepen understanding of how trauma affects survivors' health over extended periods.

This study provides critical insights into the enduring physiological consequences of trauma, even when psychological recovery appears complete. By identifying alterations in cardiovascular, inflammatory, and cortisol systems, researchers have illuminated a generalized long-term response to terrorism that transcends traditional mental health metrics. As global incidents of terrorism persist, understanding these long-term effects becomes increasingly relevant. Future investigations could explore whether these biomarkers remain distinct over time, correlate with subjective measures, or contribute to emerging health issues among survivors.